Collis. P Huntington knew he had, for the first time in his life, a fight on his hands. He wanted the breakwater built at Santa Monica for the very obvious reason that the Southern Pacific had a monopoly there. So confident was he that he could whip Congress into line that he went ahead and built a wharf nearly a mile and a half long going out from the narrow point of land where the road turns into the Malibu. For years it stood there empty and forlorn, growing gray and salt-crusted in the surf spray, a play-ground for children—a convenient fishing place for the Sunday excursionists. Finally, in the winter storms, its worm-eaten piles broke and drifted ashore to make sputtering green- and orange-colored fire logs for the movie colony at Malibu. Nothing burns like driftwood and broken ambitions.

—Harry Carr, Los Angeles, City of Dreams,1935

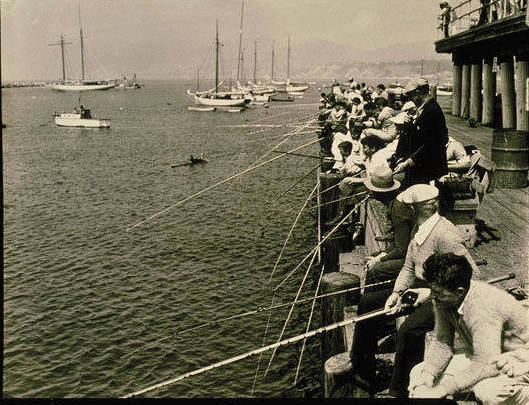

Fishing had by that time become the only major activity on the Long Wharf. At the bait house run by R. A. Muller several hundred fishing poles and tackle were available for rent to the public. On August 17, 1917 a sensation was created when the biggest halibut to be caught in several years was taken. It weighed 62 ¼ pounds, measured 4 feet 2 inches across the back and 5 feet 8 inches from its snout to the end of its tail, and was 40 minutes in the catching.

—Ernest Marquez, Port Los Angeles, A Phenomenon of the Railroad Era

In response to the increase in tourism, an announcement was made in January of 1898 for construction of a pleasure pier at the foot of Railroad Avenue. However, the city refused to give a franchise for that site (they felt it was too close to the old wharf and Southern Pacific’s rights to that site). Instead, a new group decided to build a pier near the North Beach Bath House. Work began in July of 1898 and the 700-foot-long North Beach Pier opened to tourists and fishermen in August.

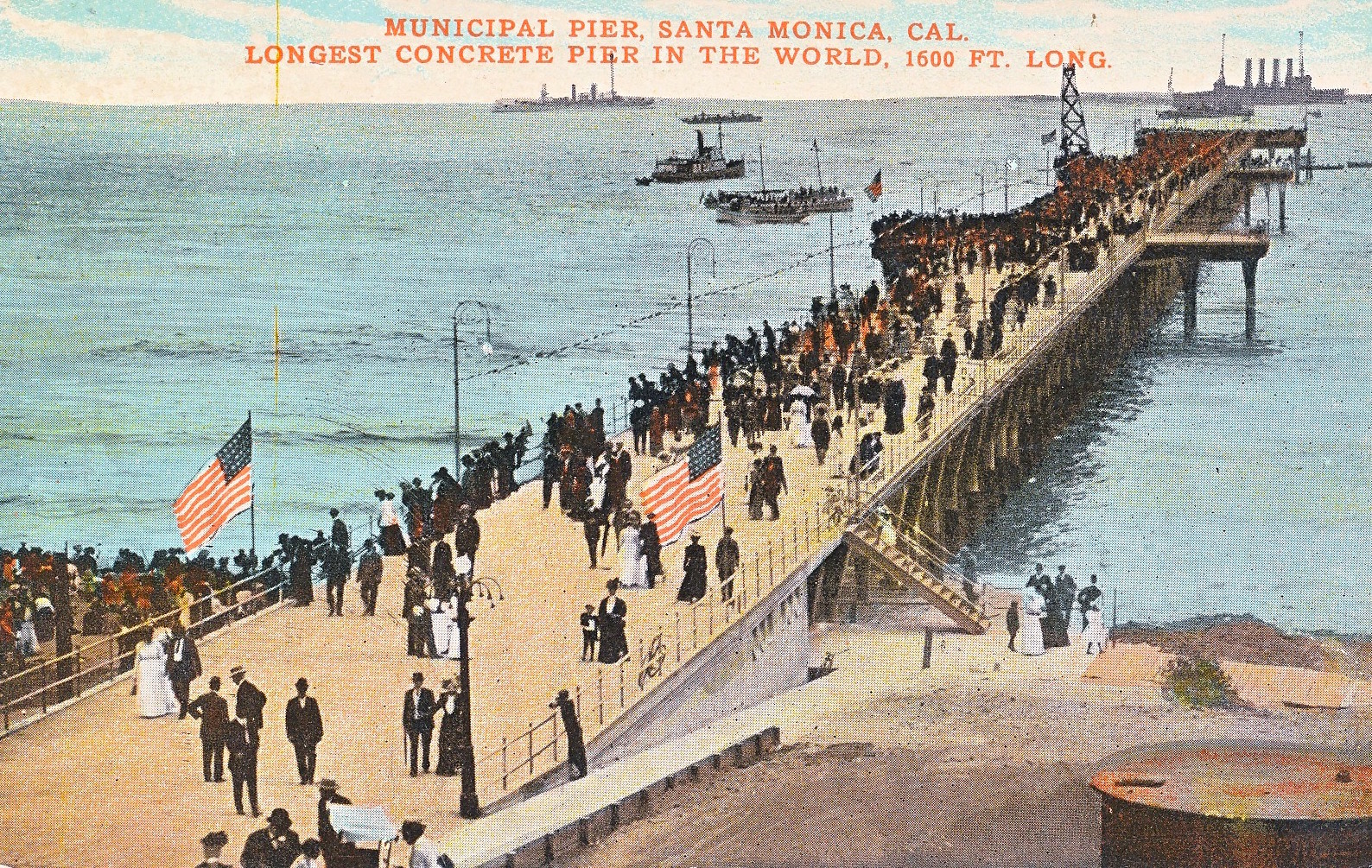

Santa Monica Pier — 1908

The best was yet to come. Between 1908 and 1909 Santa Monica built the Santa Monica Municipal Pier, a pier designed with dual roles. The main role was to provide support for sewage outfall pipes. Santa Monica was growing and, like most towns, decided to use the ocean to dispose of its untreated waste. A long structure was needed since discharge would be out past the breakers. Hopefully, waste would be carried out to sea rather than returned with the incoming tide. The second purpose for the pier was recreation, primarily angling. In March of 1905 a fierce storm had destroyed the North Beach Pier. It was rebuilt but many felt a larger pier would be useful (which proved true when an additional storm in 1908 once again damaged the North Beach Pier and finally caused it to be declared unsafe). Undoubtedly many in Santa Monica had also seen the success of other municipal piers such as the one at Long Beach.

The new pier was built at the foot of Colorado Street. When it opened on Admission’s Day, September 9, 1909, the 5,000 spectators (along with a flotilla of Navy warships and local smaller craft) saw a pier that was 1,600-foot-long and 35-foot-wide. It also contained three 40’x90’ ‘T’ shaped platforms built at 500 feet intervals from the end. The pier had a concrete deck and was one of the first piers on the west coast to utilize pre-cast concrete pilings.

Festivities that first day included a parade, a band concert, swimming and surf boat competitions, and a high diving contest from the 21-foot-height of the pier above the water (which would never be allowed today). That night, King Neptune visited the lighted pier and was asked why he had destroyed so many piers in Santa Monica Bay. He replied that he did it for the fun. His Queen announced that the new pier was concrete and indestructible—so his fun was at an end. King Neptune was ordered back into the depths and his Queen took his spot on the throne. Flame erupted from a 65-foot-high tower and King Neptune, covered by flames, leaped into the sea. Fireworks capped off the evening. Everyone evidently had a great time.

Fishing was, of course, one of the main activities on the pier and history records the “Fisherman’s Special” that was a weekend feature on Henry Huntington’s “crimson chariots.” The red streetcars, loaded with anglers and all their tackle, departed from Los Angeles promptly at 5:00 A.M., headed to the coast and its fishing piers.

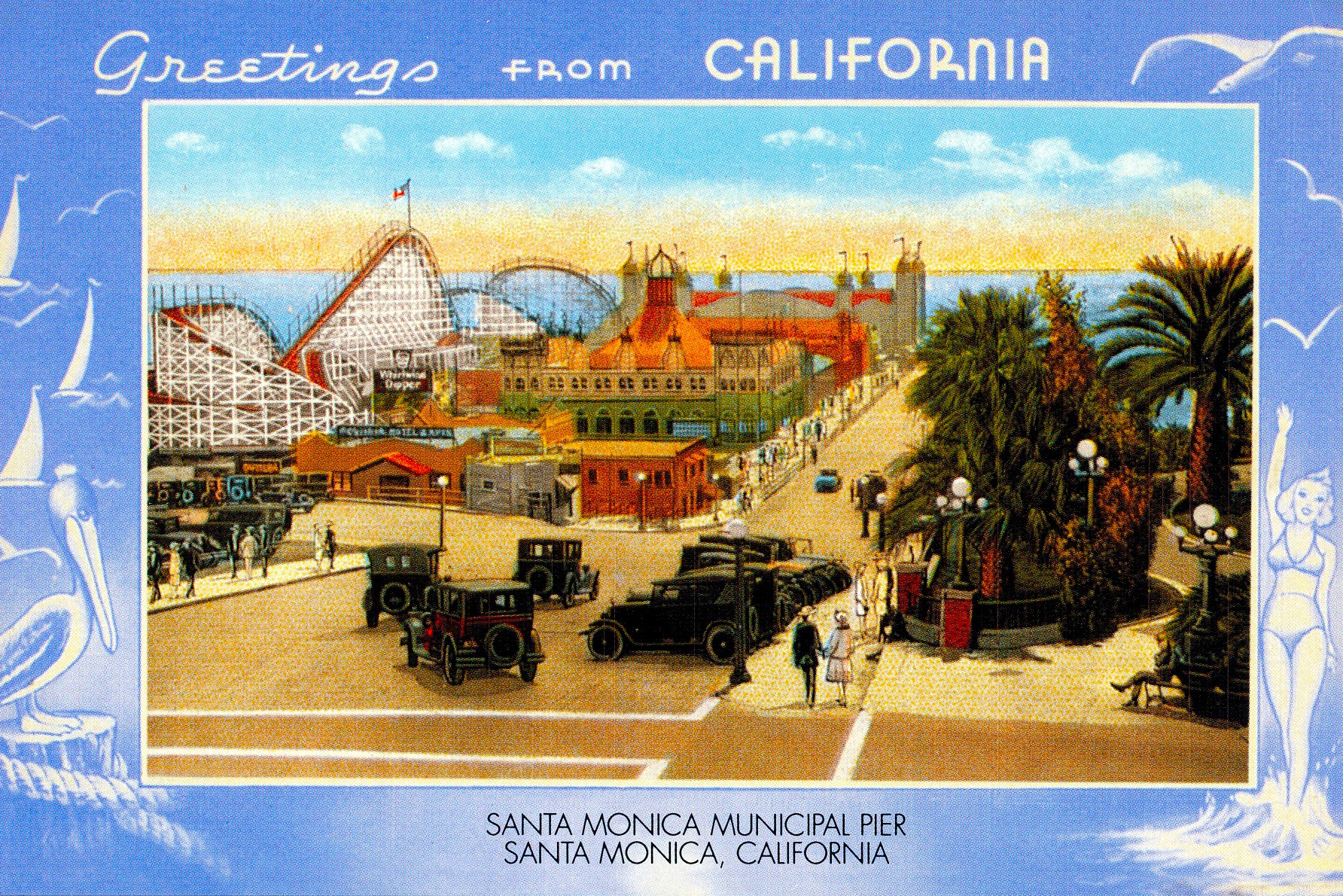

In 1911, after Fraser’s “Million-Dollar Pier” opened in the Ocean Park area of Santa Monica, several new amusement piers were proposed. None were built until Charles I.D. Looff arrived in Santa Monica in 1916. Looff had a long history as a builder and operator of amusement carousels (including Coney Island) and operated the Looff Carousel at the Pike Amusement Zone in Long Beach. He had built a carousel at the nearby “Million-Dollar Pier” but the fire on the pier destroyed it in 1912. In 1914 he had asked Long Beach for permission to build a new amusement pier near the Pike. His request was denied. Santa Monica was more receptive and he was awarded a franchise to build a pier adjacent to the already built municipal pier.

On March 25, 1916, construction of the Looff pier began. Looff’s Carousel & Hippodrome (a Byzantine styled, two-story high building) opened on June 10th. The Blue Streak Racing Coaster opened on August 2nd. The same month two more rides, the Whip and the Aeroscope rides, were opened. The 700’x267′ pier quickly became one of the premier entertainment piers in the state. That winter he opened a bowling and billiards building. The next spring and summer saw the installation of a fun house and a bandstand. Soon after, Charles Looff died, but his pier already was a success.

On August 17, 1919, thousands of people were on the Municipal Pier to view and visit a large fleet of Navy vessels anchored in the bay. During the afternoon, the north side of the pier suddenly trembled and sank two feet lower than the main deck. Although many panicked, no one was hurt. On September 4 the pier was ordered closed for sixty days and engineers began to examine the pier and pilings. In November, the pier was condemned. Nearly 200 of the pilings were rusted, cracked or entirely gone. The contractor had improperly mixed the concrete. Work started on a new Municipal Pier on March 30, 1920, a pier using creosoted wood pilings. The new pier, now widened and lengthened to 1,640 feet, officially opened on January 19, 1921.

Although the Palisades Pavilion dance hall was opened on the Looff Pier in 1921, business declined in the early 20s. In 1924, the Looff family sold their pier to the Santa Monica Amusement Company and shifted their attention to the amusement zone at Santa Cruz. The new owners soon replaced the Blue Streak Coaster with the larger Whirlwind Dipper roller coaster. It opened on March 30, 1924. Next they built the La Monica Ballroom, a huge 227’x180′ building whose gray Spanish stucco was capped with a dozen towers. At night each tower was lighted by hundreds of lights. The ballroom had room for 10,000 dancers and spectators and was highlighted by a 15,000 square foot maple dance floor containing elegant inlaid patterns. Up above, thirty-six bell-shaped chandeliers hung suspended by gold rope. On the wall was depicted a submarine garden. The intended affect was to make dancers feel like they were dancing on the coral floor of the sea. 25,000 people visited the pier the night the ballroom opened on July 23, 1924, and La Monica was an instant hit and would remain so for a decade.

In the 1920s fishing became an even bigger attraction at the Municipal Pier. In 1921, T.J. Morris first began his Sportfishing operation. By 1925, his Morris Pleasure Fishing Company operated five boats from the pier of which three were regular Sportfishing boats: the Palisades, the Ameco and the Wiko; the Myle and Lark were charter boats. The Norwahl, a fishing barge, was anchored a short distance from the pier. Competition existed on the pier. A.A. Hernage operated two boats—the Colleen and Freedom. The Owl Boat Company operated the Guilio, Cesar, Virginia and Kitty A. By 1928, the barge fishing fleet had expanded to four boats—the Fox, Minnie A Caine, Charlie Brown and the Norwahl.

“My brother Todd and I used to wake up at 4 am and hurry to the pier to get on a bait boat and haul bait. When we turned 14 or 15, in the summer, we could go out on fishing boats and help the crew with the customers. We could also fish and later sell our fish and the crew’s catch. After school at the John Adams Junior High School, we would haul fish for passengers from the pier landing to the parking lot by the La Monica Ballroom. We used a heavy hand truck and got 10 cents a sack.

Fish were so plentiful you could catch a Black Sea Bass from the end of the Pier. Once in a while we would get picked up by the police for fishing without license. The police would put our fish on the back of their trucks and take us down to the station. There they would lecture us and finally let us go, but our box of fish would be empty.

On Labor Day, a fishing boat called Amico capsized, and 16 people drowned. I was supposed to go out on that boat, but it was so full, a buddy and I went home and learned about the accident later. We raced down to the Pier, and I stood with a brick in each hand to stop the curiosity-seekers from blocking the ambulances. A big cop named Chris Christianson walked by and said, ‘Nice job kid.’ My brother gave all his clothes to survivors, but ended up in overalls. He also gave artificial respiration to a young lady, but she didn’t make it. The boat Freedom rescued many survivors without lifejackets, but also became dangerously overloaded. Other boats from the pier raced to help other survivors.

I washed dishes at the Fishnet Restaurant on the Pier, the fishing barges Minnie a Caine and Charlie Brown (owned by Olaf Olson) for a $1/day and all I could eat.”

—Karl Rydgren, I Remember, Unpublished Ms., 1975

A huge storm in February of 1926 destroyed the landing stage at the end of the Municipal Pier and soon wrecked the end of the Looff Wharf by the La Monica Ballroom (pilings were first pulled loose from the bottom and then hammered into other pilings). Then, in April a new storm tore loose most of the boats moored to the Municipal Pier. The ballroom and pier were soon rebuilt but as a result of the storms, plans began to be developed for a breakwater to be built 2,100 feet offshore. It would provide protection for the pier and provide a safe anchorage for boats.

For ordinary fishing purposes… the Santa Monica municipal pier waters have a vast quantity of bass, barracuda, yellowtail, halibut, sea trout and other small catches. The fishes average from three to eight pounds. Those with the greatest appetites, to judge from recent hauls, are the barracuda. They are coming in larger numbers than bills at the first of each month.

—Along The Fish Trail with Line N. Sinkur, Los Angeles Times, August 7, 1927

On September 11, 1931, voters approved a Breakwater Bond Measure but it would be nearly three years later, not until August 5, 1934, that the breakwater and harbor would be officially dedicated.

Fishing from the pier in 1935

In 1928 the Looff Pier was sold once again. The new owners then asked for a 200-foot extension to the pier and permission to base the Santa Monica Yacht and Motorboat Club on the pier. Over the objections of the Sportfishing interests on the Municipal Pier, permission was given with the stipulation that 197 feet of free public fishing space had to be reserved for anglers.

In May of 1930 several incidents prompted officials to question regulation of the sportfishing fleet. Soon a new loan franchise was offered by the city and it was granted to Captain Olaf C. Olson who also had a small landing on the Looff Pier. He subleased space to the Owl Boat Company, the Hernage family, and to the Morris Fishing Fleet. Late that year they were joined by Charles Arnold, who converted his 300-foot-long Kinelworth into the fishing barge Star of Scotland. He soon operated water taxi service from both the Santa Monica Pier and Ocean Park Pier to his fishing barge. (The Star of Scotland would later gain a more notorious reputation when it was converted into the gambling ship Rex. The infamous war of 1939, between the state and the gambling ships anchored three miles offshore, was finally resolved after a nine-day siege of the Rex by a flotilla of Fish and Game boats.)

Santa Monica brings back some good memories, especially when I would go with my younger nephew fishing under the restaurant at the end. Always caught something, even if the day sucked for other fishermen. Under the Mariasol, I have caught my fair share of black, walleye, shiner( not common) and rainbow perch alongside sargo, black croaker, sand and calico bass. Have also caught Bonito, mackerel, halibut, turbot, sharks and rays, and the odd eel or octopus and crabs. That pier has a lot depending on the season, though I have had some good luck with Corbina and yellowfin croakers on the north side in front of the arcade facing the breaker waves. Sand crabs and mussels are key. If you fish the middle part of the pier under the pilings on either north or south sides in the spring, one can get some solid sargo action off mussels, bloodworms, or ghost shrimp.