When anglers think of Manhattan Beach they think of the Manhattan Beach Pier, a pier first built in 1920 and one that has survived storm damage, multiple repairs, and renovations. It’s an icon in the city and has been declared a state historic landmark.

Less remembered are the two wooden piers that preceded this pier. The first, built in 1901, was at Center Street (later renamed Manhattan Beach Boulevard); it was sometimes called the Center Street Pier but over time was more commonly known as the “Old Iron Pier” since it was constructed from used railroad ties. It was the true precursor to today’s pier. It was totally destroyed by a rampaging storm in 1913 and would not be replaced until 1920

The second pier was one built in the area of 33rd and 34th Streets and called Peck’s Pier or Peck’s Pier and Pavilion. It was built in 1906 (although some sources give an implausible 1908 date). Pecks Pier was reportedly also destroyed in the 1913 storm and the nearby Pavilion was reportedly destroyed in 1920 due to “timber rot.”

Peck’s Manhattan Beach Tract

Sidewalks, Gas and Water in; Streets Graded

Handsome Pavilion Just Completed

Electric and Steam Roads Through the Tract

Lots $350 to $800

—Los Angeles Times, July 2, 1905

Manhattan’s New Pier

Manhattan, June 28. —At North Manhattan, just above the Peck pavilion, a new pleasure pier is nearing completion. It extends into the sea for a distance of more than 700 feet, and will prove of great utility to the fishermen who frequent this beach. It is the first pier along the beach south of Hyperion, and will during the season, accommodate the seaside cottages of the North Manhattan beaches.

—Los Angeles Times, June 29, 1906

Like most piers, it would see occasional damage from winter storms. A report in the Los Angeles Times of November 17, 1907 said, “from the pleasure pier at the foot of Santa Fe avenue more than twenty piles were washed, while three were wrenched out of the Manhattan structure, and one from Peck’s pier at North Manhattan.

The story of Peck’s Pier could simply be the story of one more small pier that appeared along California’s coast, lasted for a few years, and was destroyed by storm never to reappear. But the actual story of Peck’s Pier is much different; Peck’s Pier and Pavilion, and the nearby Bruces’ Beach have been surrounded in controversy since their inception. Why? Some background is needed.

George Peck who built the pier and pavilion was a wealthy real estate promoter and one of the most influential men in the early history of Manhattan Beach. In fact, the name for the city, Manhattan Beach, resulted from a coin flip between Peck who was calling his early development Shore Acres (after the name on the Santa Fe Railroad junction) and another developer, John Merrill, who was calling his development Manhattan (after his hometown). They decided it was confusing potential buyers and in 1903 they flipped a half dollar coin to determine the name. Merrill won the coin toss, the city became Manhattan Beach, and the railroad changed the name on its sign.

Peck built Peck’s Pier and Pavilion (open for dances, parties and roller skating) as a way to attract buyers to his development. It was the same strategy used by most developers along the coast. In fact, almost every beachfront town in the early 1900s saw a pier, dance pavilion, and other attractions such as saltwater plunges and golf courses; the attractions were built to attract buyers.

What was different about Peck’s Pier was that we think it was open to all people, including blacks, the only pier along Santa Monica Bay at the time with such a policy, and its story is more about sociology, race relations and racism than about fishing.

When Manhattan Beach was incorporated in 1912, Peck bucked the practices of other real estate developers by opening two blocks of land to sale to African-Americans. The land, fronting the ocean between 26th and 27th Streets and Highland Avenue, would become, in time, contentious on many fronts.

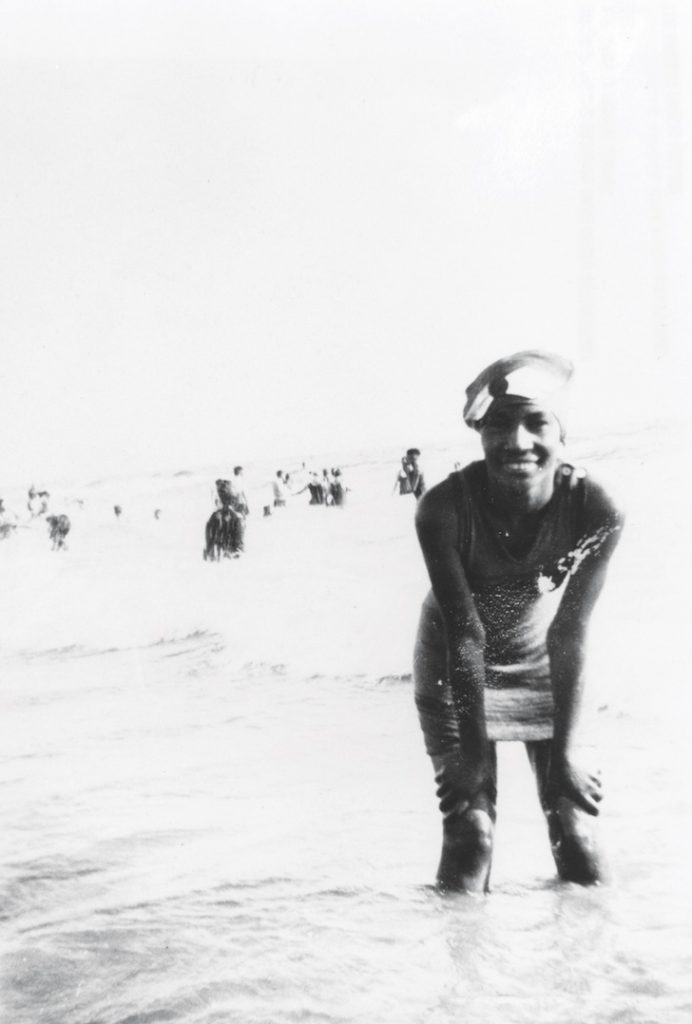

Within a short time Charles and Willa Bruce built a small resort on the beachfront property, and it would be the only resort on Southern California’s beaches open to blacks. Amenities included tents for showering, bathing suits, dining and dancing. Blacks could now travel to Manhattan Beach on the Pacific Electric trains, spend a day at the beach, and even spend the night at the resort. Other black families also built summer homes in the area and the beach itself became known as Bruces’ Beach. (The only other beach open to blacks on Santa Monica Bay was the so-called Inkwell in Santa Monica located at the western end of Pico Boulevard and stretching two blocks south to Bicknell Beach. A proposal to build a resort near the Inkwell in the early ‘20s was blocked by Santa Monica.)

Apparently from an early time pressure grew for Manhattan Beach to shut down the black area and the KKK organized a campaign to drive the families out of town. Stories told of cross burnings, slashed tires, anonymous phone calls, “10 minute parking only” signs placed near resident homes, and white homeowners on both sides of Bruces’ Beach roping off their beach areas. Homes were burned while the Fire Department stood by and did nothing.

Some reports give the pier being destroyed in the winter storms of 1913. However, it was probably rebuilt given that newspaper advertising suggests the pier, bath house and pavilion were still in existence in mid-1920.

Peck’s-Manhattan Beach

Free Excursion

All Come—Free Lunch

Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Saturday

Busses leave 424 West Sixth Street, 10:30 a.m.

We will sell 100 choice Ocean Beach Residence Lots, Just on the Market, at Special Bargain Prices.

Lots Within 900 Feet Ocean Surf, Fine View, $200

Close to Coast Boulevard and Standard Oil great $20,000,000 plant.

Terms $50 Down, $10 Monthly

Nearer Ocean Surf, With Cement Walks, $350 and $450

Peck’s-Manhattan Beach

In the coming seaside resort, 14 miles from Los Angeles. Fine sand beach, splendid electric car line, $70,000 fishing pier, $20,000 bath-house and pavilion, city water. 500 more houses needed.

But Beach Lots Now For Investment

Speculation or Summer Home

They will be USEFULL and a BARGAIN. Come in, get permit to camp on beach, Saturdays and Sundays.

Geo. H. Peck & Co.

424 West Sixth St., Opposite Park

Phone Main 7342

—Los Angeles Times, August 4, 1920

Finally, in 1924, a group of citizens of Manhattan Beach petitioned the city to condemn Bruces’ Beach and create a park. The Bruce’s and other black families sued the city to keep their property but lost in court and the city, through eminent domain, purchased the properties for $75,000 ending the suit.

In 1927 the buildings were razed and the city rented the beach to Oscar Bassonette (who ran the bait shop on the Manhattan Beach Pier) for $1 a year. He soon posted signs excluding blacks from the beach. After protest demonstrations and a swim-in by the NAACP, the city revoked the lease to Bassonette in 1927 and declared that Manhattan Beach would “forever remain open and free of access to the general public without restriction.”

Racial restrictions on other Los Angeles beaches would gradually disappear. In some ways the Bruce’s and the other African-Americans who had owned property in Manhattan Breach had lost the battle but won the war.

Manhattan Beach — Colored People’s Resort Meets With Opposition

Redondo Beach, June 24. — The establishment of a small summer resort for negroes at North Manhattan has created great agitation among the white property owners of adjoining land.

The new summer resort which at present consists of a small portable cottage with a stand in front where soda pop and lunches are sold, and two dressing tents with shower baths and a supply of fifty bathing suits, was opened last Monday by the dusky proprietor and patronized by many colored people from Los Angeles.

Yesterday when a good-sized Sunday crowd of pleasure seekers had gathered and donned their bathing suits to disport in the ocean, they were confronted by two deputy constables who warned them against crossing the strip of land in front of Mrs. Bruce’s property to reach the ocean.

For a distance of over half a mile from Peck’s pier to Twenty-fourth street, a strip of ocean frontage is owned by George H Peck, who also owns several hundred acres of land in the Manhattan addition where Mrs. Bruce’s property is situated. This strip has been staked off and “no trespassing” signs put up and consequently the bathers yesterday could not get to the beach without walking beyond Peck’s strip of ocean frontage.

This small inconvenience, however, did not deter the bathers, on pleasure bent, from walking the half-mile around Peck’s land and spending the day swimming and jumping into the breakers. All along the beach in front of the prohibited strip, which was patrolled by the constables, the light-hearted “cullud” people frolicked in the breakers or lay on the warm sand enjoying the sea breezes.

Mrs. Bruce, a stout negress whose home is at No. 1021 Santa Fe avenue, says most emphatically that she is there to stay, and that she will continue to rent her bathing suits to people of her race. She owns a lot on Manhattan Avenue, 33×100 feet, for which she paid $1225, a high price compared to the cost of nearby lots. She says she purchased the property from Henry Willard, a real estate dealer in Los Angeles.

The entire next block in the Manhattan addition between Twenty-sixth and Twenty-seventh streets has been leased to Milton T. Lewis, a colored real estate dealer by Willard. Lewis proposes to rent space for tents on this block to negroes who desire to come to the beach.

The situation as described by Mrs. Bruce, has a pathetic side, for she avers negroes cannot have bathing privileges at any of the bath-houses along the coast, and all they desire is a little resort of their own to which they might go and enjoy the ocean. “Wherever we have tried to buy land for a beach resort we have been refused, but I own this land and I am going to keep it.”

She and her associates feel that it is unjust that they should not be allowed to “have a little breathing space” at the seaside where they might have a holiday.

Her husband is a chef on a dining car that runs between Salt Lake City and Los Angeles.

Property-owners of the Caucasian race who have property surrounding the new resort deplore the state of affairs, but will try to find a remedy, if the negroes try to stay.

—Los Angeles Times, June 27, 1912 [Copied as written]

Is the generally accepted story accurate? Did Peck actually open up the land, beach and his pier to blacks? No one at the Manhattan History Society can give a definitive answer but some black critics argue against the praise he has been given.

A story reported in The Easy Reader News on May 5, 2016, titled “Prejudice, lies and history in Manhattan Beach,” gives a critical and different view of Peck. It says, “the story was blurred and mythologized to salve the feelings of the predominantly white community. The plaque that marks the site of the resort begins with a complimentary mention of George Peck, the real estate mogul who developed much of Manhattan Beach, praising him for selling to someone who wasn’t white. This is odd because Peck probably had nothing to do with it: a contemporary news article credits the sale to George Willard, a different real estate agent. If, as the inscription says, Peck did set aside land for a non-white development, he evidently changed his mind quickly. When Bruce’s Beach opened, a pair of “volunteer deputy constables,” one of whom was Peck’s son, roped off the direct access to the beach. The bathers at Bruce’s Beach had to walk half a mile around that section to get to the water.”

The construction of a modest black summer resort in North Manhattan has caused a lot of concern among the white landowners who own adjacent properties.

I appreciate your insights on the historical significance of the fishing piers in Manhattan Beach! For anyone interested in enjoying some thrilling activities and experiences, I recommend checking out 1xbit. They offer an exciting platform with a variety of games and features that can enhance your leisure time. Engaging with their services has certainly added a fun twist to my own experiences, providing ample opportunities for enjoyment. Don’t miss out on what they have to offer!

Thank you for providing information about Peck’s Pier & Bruce’s Beach in Manhattan Beach—Gone But Not Forgotten! I appreciate the insight into its history.

This article provides a fascinating glimpse into the lesser-known history of Manhattan Beach, highlighting the forgotten piers and the controversies surrounding Peck’s Pier and Bruces’ Beach. It’s a great reminder that history is often more complex than we realize.

This piece beautifully uncovers the layered history of Manhattan Beach—especially the forgotten legacy of Bruce’s Beach and Peck’s Pier. It’s both inspiring and heartbreaking to read about the resilience of the Black community amid such blatant injustice. Thank you for preserving and sharing this essential part of California’s coastal story

The Manhattan Beach Pier, a state historic landmark, is the most recognized, having been rebuilt and renovated multiple times since its original construction in 1920 after surviving significant storm damage.

Before the current pier, two earlier wooden structures existed: the “Old Iron Pier” (built 1901) at Center Street, which was destroyed in a 1913 storm, and Peck’s Pier (built 1906), also reportedly destroyed in the same storm.

The history of Manhattan Beach’s piers reveals a pattern of resilience against natural forces, with earlier structures succumbing to storms and timber rot before the enduring 1920 pier became the iconic landmark it is today.

The establishment of a tiny black summer resort in North Manhattan has generated

significant apprehension among the white homeowners of neighboring homes.

What a fascinating history. It’s sad that Peck’s Pier is gone, but the stories live on. The names “Peck’s Pier” and “Bruce’s Beach” have such a classic ring to them, full of history.

Thanks for sharing this piece of local history. It’s captivating to read about what these places were like back in the day.

That’s a fascinating bit of history about the Manhattan Beach Pier! I had no idea there were two piers before the current one. It’s amazing to think about how resilient the current pier is, especially after hearing about the “Old Iron Pier” being completely destroyed by a storm. Makes you appreciate the engineering and constant upkeep. Visiting the pier now, it’s hard to imagine the beach without it – almost like imagining a world without, say, an Eggy Car! It’s just a local landmark, integral to the area’s identity.